A Momentarily Comprehensive Guide to Prediction Markets

Inside the race to build Kalshi, Polymarket and a $100 billion-plus asset class

I think there’s an interesting misalignment between how the media talks about Kalshi and Polymarket, and how the two companies’ investors probably view them.

The media’s focused on how prediction markets are upending the sports betting industry. I’ve seen endless commentary on Kalshi’s growing NFL volumes, sportsbooks’ plummeting stocks, Kalshi & Polymarket’s NHL deals, and DraftKings’ acquisition of the CFTC-licensed startup Railbird.

Of course, sports are a large part of prediction markets’ current hype cycle. Since the start of NFL season, sports have made up around 90% of total Kalshi trading volume.

But I think Kalshi and Polymarket’s investors are paying much less attention to sports than the media thinks. Sequoia and a16z recently backed Kalshi at $5 billion – and Kalshi’s now seeking a $10-12 billion valuation. Intercontinental Exchange just backed Polymarket at $9 billion, after Founders Fund led a round – and Polymarket’s now seeking a $12-15 billion valuation.

The world’s most prestigious megafunds have high bars for investing anywhere outside AI. On every investment, they have to underwrite a venture-scale return (i.e. 5-10x minimum) to help return their megafunds. And if they’re backing Kalshi and Polymarket between $5 - $15 billion valuations, the sports betting TAM simply isn’t large enough. DraftKings, the largest US sportsbook, has a $15 billion market cap. Flutter, the world’s largest online betting company, has a $40 billion market cap – and that’s been a 25-year journey.

So what is the grand ambition of Kalshi, Polymarket and their VCs? And is it realistic?

That’s what I’ll explore in this essay: A Momentarily Comprehensive Guide to Prediction Markets. I say “momentarily” because the space is moving so quickly. But I say “comprehensive” because I’ll try to address all the most important issues at play.

In Part 1, I’ll explain what grand vision Kalshi, Polymarket and their VCs see – and why that vision is so tied up in wildly unpredictable American politics.

In Part 2, I’ll explore who’s most likely to emerge from the chaos as the dominant US sports prediction market.

In Part 3, I’ll share where I’m most excited to see innovation around prediction markets as an early-stage investor.

Part 1: What’s the grand vision, and why is it tied up in American politics?

The grand vision of Kalshi and Polymarket is for prediction markets to establish a new, massive financial asset class.

The best comps aren’t sportsbooks with $10 - $40 billion market caps. They’re financial exchanges with $50 - $150 billion market caps. As examples…

Intercontinental Exchange, which owns the New York Stock Exchange, is worth $83 billion.

CME Group, the world’s dominant futures & options exchange, is worth $96 billion.

Binance, the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, is worth $150 billion.

These companies all make money by operating the core infrastructure of global markets. They match buyers and sellers, clear trades, and monetize data and fees from every transaction.

Kalshi and Polymarket are far from the size of these giants. In October, Kalshi and Polymarket processed $7.4 billion in combined volume. For perspective, the NYSE processed $134 billion over the same period.

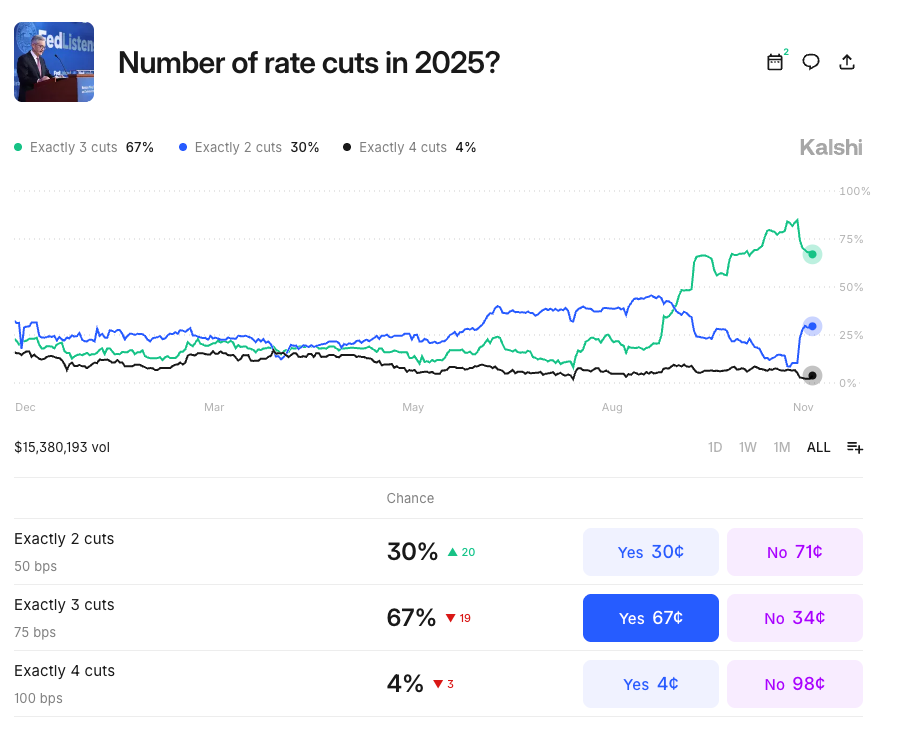

But Kalshi and Polymarket believe in a future where, just like institutional and retail investors trade equities, options and crypto, they also trade event contracts. Hedge funds like Bridgewater will make macroeconomic bets on the number of Fed rate cuts. Corporates like Nike will hedge geopolitical risk by betting on new China tariffs. Retail investors will trade their own dollars on the NYC mayoral election.

Kalshi and Polymarket also believe in a future where prediction markets are a source of truth for society. If you talk with any prediction market nerd like Polymarket CEO Shayne Coplan, they’ll point you in the direction of a Nobel Prize-winning 1945 essay by FA Hayek, “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” That essay essentially argued that decentralized markets can aggregate information and drive prices more accurately than any centralized planner. Or framed as a practical example, a prediction market can predict the result of a presidential election better than any poll or media outlet. Coplan likes to emphasize that Polymarket predicted Trump’s 2024 victory well before the polls and media did.

In the not so distant future, it’s possible that consumers will view Kalshi or Polymarket odds as the ground truth probability of any major event – from the Chiefs winning the Super Bowl, to Taylor Swift having a child, to the Fed raising rates. If The Wall Street Journal writes about Tesla today, they’ll embed Tesla’s stock ticker in the article. That stock price is seen as an objective metric for company performance. If event contracts gain the same credibility, the Journal could one day include in the same article the Kalshi odds of Tesla hitting delivery quotas this quarter.

You could even imagine Kalshi or Polymarket becoming a “dictionary word company.” Just like you’d Google Taylor Swift’s tour dates, you’d check the Kalshi of when she’ll release her next album.

Long-term, sports could be the most-traded type of event contracts. If you think about it, sports are society’s largest category of events that 1) happen all the time and 2) people care about. (Side note: That’s also why sports are single-handedly propping up cable TV). But the challenge is Kalshi and Polymarket will have the hardest time legally justifying sports events as financial markets and not gambling.

Which brings us to the massive legal, political and moral question that will determine the future of prediction markets: Are event contracts financial instruments under federal CFTC regulation or gambling under state regulation?

That question is at the center of the entire prediction market hype cycle. Unlike in AI, prediction markets haven’t exploded because of new technological innovation. Sports betting exchanges have existed internationally (e.g. Betfair) and even in certain US states (e.g. Sporttrade) for years now.

Prediction markets have exploded because of regulatory arbitrage. In 2023-24, Kalshi sued the CFTC and won a federal appeal, which decided that event contracts around Congressional elections were not gambling activity. Then last November, Donald Trump won the White House, the CFTC voluntarily dismissed its appeal, and Kalshi took the bold step of launching sports contracts in January.

Polymarket’s had a slightly different path. Whereas Kalshi feels like a fintech platform – taking bank deposits and requiring KYC – Polymarket has a blockchain protocol and takes crypto deposits. But they’ve similarly benefited from Trump’s regulatory regime. Just under a year ago, the Biden administration treated Polymarket as a bad actor when the FBI raided the New York apartment of Shayne Coplan. Today, under the Trump administration, Polymarket is preparing for their reentry into the US and Coplan is the world’s youngest self-made billionaire.

If you squint, there might be some intellectual honesty behind the Trump CFTC’s green-lighting of Kalshi and Polymarket. Trump’s entire ethos is anti-establishment. Prediction markets are inherently anti-establishment, as they let the masses, not institutions, identify the ground truth. There’s also a legalistic argument for event contracts as financial markets. Just as traders can bet on future oil prices to manage risk and discover information, they should be able to bet on future events.

But that said, there’s a lot of self-dealing going on in the White House. Donald Trump Jr. is an advisor to both Kalshi and Polymarket. Trump megadonor Charles Schwab is an early backer of Kalshi, and Peter Thiel’s fund backed Polymarket. Trump’s first nominee for CFTC chair Brian Quintenz was Kalshi’s lawyer. And if that wasn’t enough, last week Trump’s Truth Social announced they’d add prediction markets to the platform. Meanwhile, the Republican-controlled Congress is following Trump’s lead and not pushing any legislation to regulate prediction markets.

At the same time, multiple state gaming boards and tribes are suing Kalshi on the grounds that sports and election contracts are unlicensed gambling infringing on their jurisdictions. Just last week New York became the largest state to enter the mix when their gaming commission sent Kalshi a cease-and-desist and Kalshi sued.

It’s impossible to know how the regulatory environment will shake out. We don’t know who will control Congress after 2026, or the White House after 2028, or the Supreme Court whenever a case lands there.

In my opinion, the even larger but less-discussed question is how American consumer and voter sentiment will respond to the explosion of prediction markets. There’s a lot to like. For example, I live in New York City where we’ve had a big mayoral race. Over the last couple months, I’ve come to appreciate Kalshi as a more accurate bellwether of Zohran vs Cuomo’s odds than any polls or reporting from past elections.

But I’d argue there are a whole lot of things that can, and will, go wrong. To name a few…

Insider trading is one major problem. For example it’s virtually impossible to police insider info around “mention markets,” where you bet on whether a public figure will say certain words. Last week on Coinbase’s earnings call, Brian Armstrong pulled up Kalshi and Polymarket’s mention markets and rattled off every word that was listed. $84K was in that market. It’s clear the CFTC doesn’t have nearly as many enforcement resources as the SEC, and Kalshi and Polymarket aren’t taking the burden on themselves to ensure fair markets.

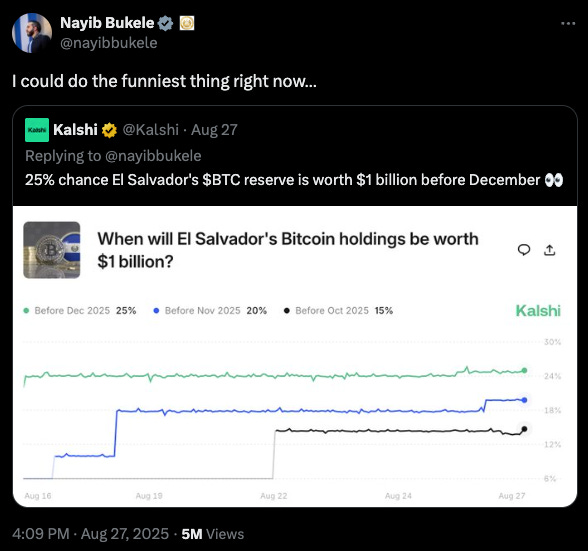

In August, El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele retweeted a Kalshi market around El Salvador’s Bitcoin holdings and Bukele commented “I could do the funniest thing right now…” Kalshi’s CEO retweeted that, saying “World leaders are using Kalshi and you’re bearish?” Imagine if Tim Cook joked about tanking Apple stock or Patrick Mahomes joked about tanking the Super Bowl.

The NBA gambling ring investigation just showed the world how insider trading could penetrate a walled garden with huge incentives to stop it. In non-sports events, insider trading gets even harder to police.

Market manipulation by bad actors is another major risk. During the 2024 election cycle, Trump constantly pointed to Polymarket odds as a sign of voter support for his campaign. In the future, a well-funded actor could take an enormous position – e.g. buying millions of dollars’ worth of “Candidate X to win” shares – to artificially drive the market in one direction and influence undecided voters. You could see parallels with how Russia manipulated American social media during the election.

Lastly, gambling addiction is another major problem. Kalshi is available to Americans ages 18+ in all 50 states – whereas online sportsbooks are available to ages 21+ in 38 states. All of a sudden, every college kid can freely bet. And worse, Kalshi has run ads calling their product “kind of addicting.” Imagine if DraftKings ran an ad saying parlays were so fun they’re addicting, with gambling addiction a growing epidemic.

Just one of these things needs to go wrong for Americans to sour on the rise of prediction markets and lack of regulation – and that could drive political blowback.

But in the meantime, Kalshi and Polymarket are moving at warp speed to raise more money, acquire more customers, and establish a massive asset class before regulatory tailwinds change. The longer Trump and his allies are in office, and the more Americans get used to prediction markets in everyday life, the harder it will be to put the cat back in the bag.

Part 2: What happens to the American sports betting industry?

So, what do Kalshi and Polymarket’s rise, and all these regulatory questions, mean for the American sports betting industry? And who’s best positioned to emerge from this chaos as the dominant US sports betting brand?

It’s important to note: there’s a real chance that courts eventually rule that sports event contracts are gambling activity outside the CFTC’s jurisdiction. In which case the sports betting industry would revert to the old status quo of state-licensed sportsbooks.

But let’s imagine the current regulatory environment holds.

In that case, the $14 billion US sports betting industry will undergo a total paradigm shift – with value shifting from state-licensed sportsbooks to federally licensed exchanges. Rarely does so much economic value shift hands so quickly.

It might not happen overnight. But bettors will eventually move from sportsbooks to exchanges. Why? Sportsbooks have business models that are inherently adversarial to bettors. Bettors bet against the house, which makes money by baking a margin (a “vig”) into every line. Hence sportsbooks kick winning bettors off their platforms.

But exchanges have a more bettor-friendly model. Bettors bet against each other, which sets the lines, and the house makes money by taking a transaction fee on all trades. Over time, prediction markets will offer better-priced odds, which will migrate bettors over from sportsbooks.

It’s also critical to understand that sports betting and prediction markets are both inherently winners-take-most businesses.

Sports betting is winners-take-most because it’s all about customer acquisition and retention. Larger companies fuel larger marketing budgets, which fuel more revenue, which fuel larger marketing budgets, and so on. That’s why since PASPA’s repeal in 2018, two early movers, FanDuel and DraftKings, have dominated two-thirds of market share. Only recently have other brands like Fanatics started to eat away at their duopoly.

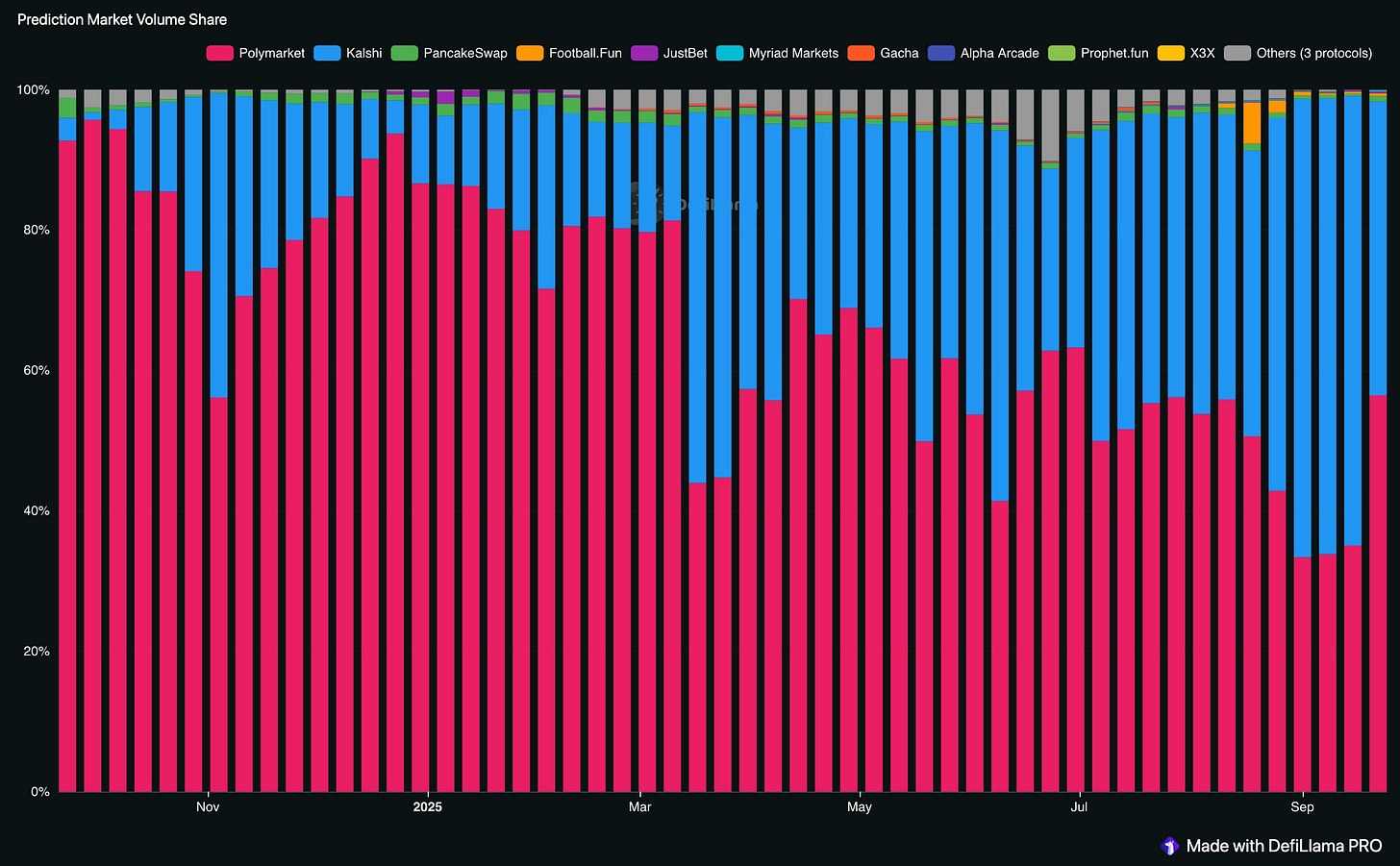

Prediction markets are winners-take-most because they’re all about liquidity. Liquidity powers tighter spreads, which attracts more traders, which attracts tighter spreads, and so on. That’s why Kalshi and Polymarket collectively comprise 98% of all volume traded on prediction markets.

Given these winners-take-most dynamics, only a few companies will emerge as the dominant sports prediction markets. So who will they be?

There’s a case that Kalshi and Polymarket will win sports. Today they have by far the most liquid sports markets, and that advantage will continue to compound. They also have head starts on customer acquisition; Kalshi’s already started flooding social media with sports ads.

But there are also reasons to doubt their long-term success in sports.

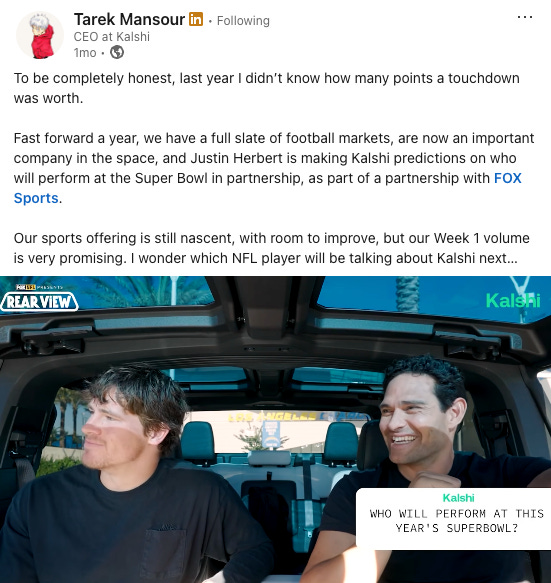

First, Kalshi and Polymarket aren’t sports betting-native companies. Compared to sportsbooks, they lack years of experience around bonusing, VIPs, personalization, and creating engaging products for sports fans. Last month Kalshi CEO Tarek Mansour said “To be completely honest, last year I didn’t know how many points a touchdown was worth.”

Second, Kalshi and Polymarket don’t just want to be sports brands; they want to host markets for macroeconomic, political, cultural and other events. It’s hard to be an everything brand but still engage sports fans. A great case study is The New York Times. They had a sports page. But as an everything brand, they had to acquire a different brand in The Athletic to engage sports fans.

The next most interesting players are the incumbent sportsbooks, like FanDuel and DraftKings. These sportsbooks have everything that Kalshi and Polymarket lack: huge user bases of sports fans and all the core competencies of sports betting businesses. They also have cheaper and more stable costs of capital as public companies.

A couple weeks ago, DraftKings made a splash by acquiring Railbird, a CFTC-licensed startup. In August, FanDuel (owned by Flutter) announced a joint venture with CME Group, the giant CFTC-licensed derivatives exchange. Flutter’s CEO also said they assigned talent from BetFair, the European betting exchange they own, to evaluate US prediction markts. Theoretically, DraftKings or FanDuel would just need to pivot their core products from sportsbooks to prediction markets.

But here’s the problem. Multiple state gaming boards have warned licensed sportsbooks that launching prediction markets, even in other states, could mean the suspension of their OSB licenses. So it’s a classic innovator’s dilemma. FanDuel and DraftKings would need to risk billions in sportsbook revenue to pursue prediction markets revenue. It’s still TBD how aggressively and how soon these sportsbooks move.

I think there’s one other category of companies with a plausible case to become the dominant sports prediction market. These are growth-stage sweepstakes and daily fantasy companies.

Underdog, PrizePicks, Fliff and others have similar advantages to sportsbooks: large user bases, core competencies needed for sports betting, and even more beloved brands. Go to any college campus and you’ll hear more students talking about Fliff than FanDuel. But these businesses have been growing in regulatory gray areas, and they’re increasingly under fire. In June New York’s AG sent cease-and-desist letters to sweepstakes operators. In October California passed a bill banning sweepstakes operators. Many other states are on similar paths.

Underdog, the DFS operator, announced they’re partnering with Crypto.com to offer sports event contracts in Underdog’s app. Novig, the sweepstakes sports exchange, said they’re going to seek CFTC approval.

I expect a wave of growth-stage sweepstakes and daily fantasy companies will raise $50 - $150 million growth rounds to pursue a CFTC license and launch as prediction markets. I wouldn’t be surprised if we see the same from state-licensed and/or international exchanges like Sporttrade and ProphetX.

The challenge is these companies will compete against better-resourced players in Kalshi, Polymarket and the major sportsbooks. And maybe more fundamentally, they can’t guarantee how long it will take to get a CFTC license. It took Railbird 2.5 years to get theirs. With a new CFTC chair nominee announced last week, it’s hard to know how loosely he’ll dole out new licenses.

So to summarize, I think the sports prediction market throne is up for grabs between Kalshi & Polymarket, incumbent sportsbooks, and growth-stage sweepstakes and daily fantasy companies. It would be near impossible for any net-new company to enter the rat race and emerge as the go-to sports prediction market.

But even with that race played out, I think there are plenty of venture-scale prediction market businesses that haven’t been started yet.

Part 3: Where do I see room for new startups to emerge?

As an early-stage investor, I see multiple opportunities to build new venture-scale businesses around prediction markets, and I’ll dive into them.

You’ll notice a theme: the vast majority of innovation in prediction markets so far is coming from the crypto community. There are a couple reasons for this.

First, there’s a deep ideological overlap between prediction markets and crypto. Both stem from libertarian, anti-establishment worldviews that value transparent, decentralized systems over hierarchical, institution-led systems. If crypto seeks to decentralize money, prediction markets seek to decentralize truth and information. That’s why a lot of crypto enthusiasts have started building around prediction markets.

Second, there are practical synergies between the two. Most prediction markets have launched offshore and with crypto, not fiat, in order to avoid uncertain regulations in the US and other countries. Additionally, as we’ve seen from the success of Stake.com and other crypto gaming platforms, crypto and betting go together really well. Betting gives crypto holders utility for their currency, and crypto gives betting platforms efficient payment rails.

So you’ll see a lot of web3 companies mentioned below.

I’ll break down the areas I’m excited about into two parts: B2C and B2B.

B2C

I think a wave of companies will take prediction market infrastructure and build net-new B2C entertainment experiences on top.

A good comp is the evolution of the US sports betting industry. In 2018, FanDuel and DraftKings quickly established themselves as the dominant sportsbooks. But in the seven years since, we’ve seen startups like Underdog, Fliff, PrizePicks and Sleeper take betting infrastructure and build highly-engaging experiences for sports fans. These companies consider themselves gaming and social companies as much as betting companies.

Similarly, I think we’ll see Kalshi and Polymarket complemented by new prediction market experiences.

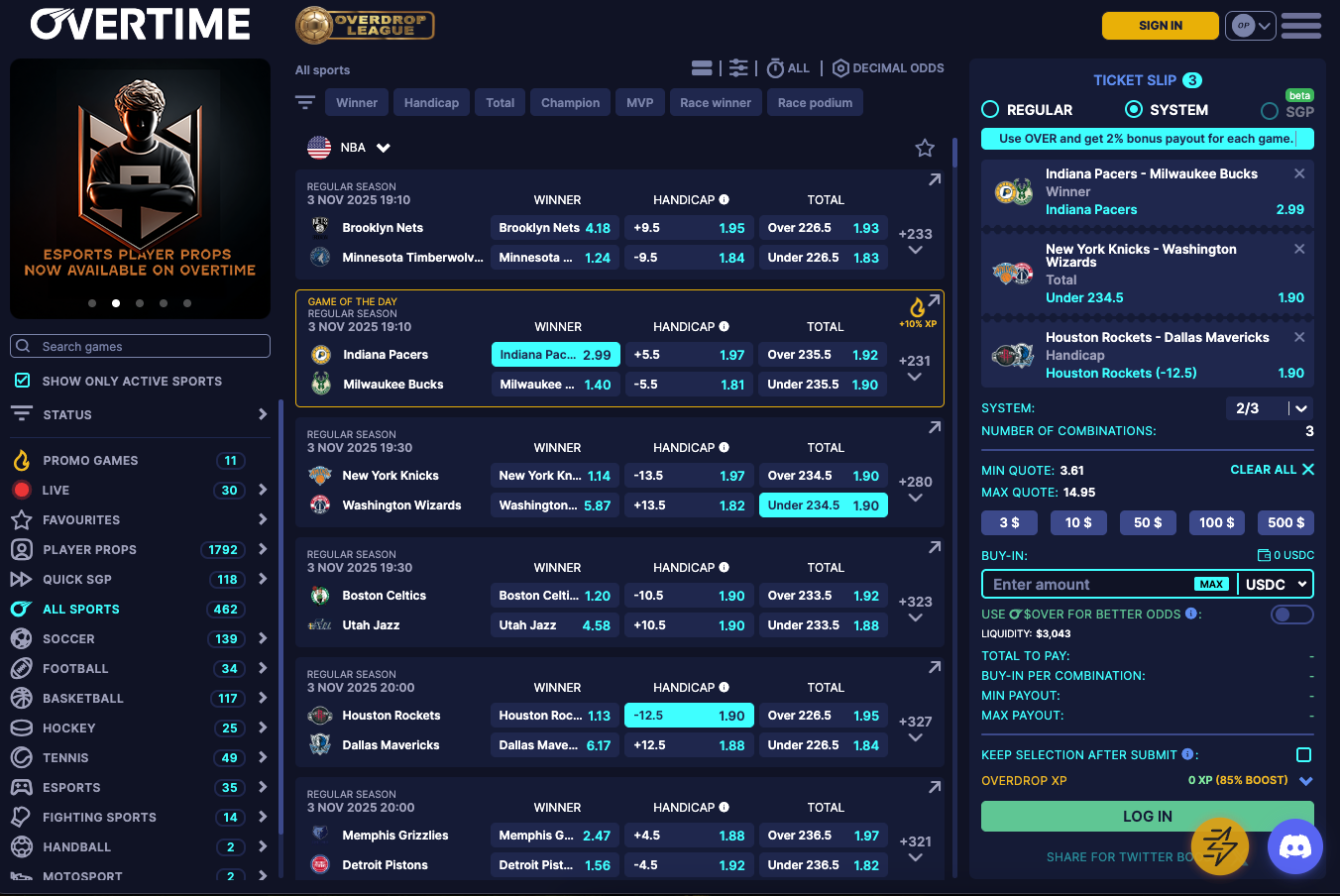

On the sports side, one product I’ve enjoyed is Football.Fun. It’s a crypto-based fantasy soccer game built on prediction market odds. You rip open player card packs, build your squad, compete in tournaments, and track your ranking. They launched in August and already have $40 million in volume on the platform. Another interesting product is Overtime. It’s an on-chain sports prediction market that focuses on parlays, with much more intuitive UI than Kalshi and Polymarket parlays. Overtime has $77 million in volume on the platform.

Outside of sports, I think casino-style games are an interesting opportunity. Eilers & Krejcick wrote an interesting blog about this. If you reduce the resolution window of any event – for example if you bet on whether Bitcoin will go up or down in the next five seconds – that essentially becomes a randomly-determined casino game. Online casino handle is roughly 20% of online sports betting globally, but a lot more profitable, so I expect more platforms to lean into casino-style games. Limitless, an exchange with $274 million in volume, already offers 30 minute resolution windows on markets and plans, and the company plans to expand to 15-, 10- and 1-minute resolution windows soon.

We could also see engaging prediction experiences built around cultural events. Maybe consumers would enjoy betting on People Magazine-esque celebrity events like they bet on sports. Last summer a Polymarket market around Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce getting engaged did $385K in volume. Maybe consumers would enjoy betting on their favorite digital creators. You could create a market. Here’s a Kalshi market around how many YouTube subs MrBeast will hit this year. These types of markets could benefit from sitting under a unique brand.

One relevant startup is Kizzy, which wants to let users bet on events like what IShowSpeed will say in his next stream. I think creators in particular are a particularly interesting distribution channel because you could incentivize them with a revshare to promote specific markets. But as mentioned above, these types of contracts also bring risks around insider information.

It’ll be interesting to see which regulatory path these new prediction market startups pursue. Some will definitely stick with an offshore, crypto approach. Others might pursue a DCM (the license Kalshi has), or an FCM (another license that essentially lets you route trades to a DCM). This will depend on how the regulatory environment shakes out.

But the bottom line is: large businesses will emerge by building new consumer-facing entertainment experiences around prediction markets.

B2B

If the B2C opportunity is about creating experiences for retail traders, the B2B opportunity is about creating tools for institutional investors.

As highlighted above, prediction markets live or die by liquidity. That’s why Kalshi and Polymarket are now heavily incentivizing hedge funds to make large bets and market makers to boost liquidity on their exchanges. (For context, market makers are specialized trading firms that constantly fill buy and sell orders, make a small spread on each trade, and keep markets liquid).

In every asset class, institutional investors rely on a large suite of tools. They pay for market data feeds to help traders make informed decisions; execution management systems to route orders across exchanges efficiently; risk management software to monitor overall firm exposure; compliance software to ensure compliance with regulations; and much more. Many of these tools are built for other asset classes (e.g. the equities market) but not for prediction markets.

One relevant startup from this YC batch is Dome. They’re building “the ultimate API for prediction markets,” providing access to prediction market data across multiple exchanges. A hedge fund or market maker could use Dome to get real-time market prices, historical data and order tracking in order to optimize their trading strategy. It’s worth noting that Kalshi and Polymarket are built on more modern tech stacks and APIs than older exchanges like the NYSE that are built on dated tech stacks, so it’ll be interesting to see how much value tools like Dome can capture.

Another interesting opportunity is in selling data feeds and predictive algorithms around event contracts. As the US sports betting industry emerged, Sportradar and Genius Sports built large businesses brokering game data and providing odds suggestions and pricing models to sportsbooks. Prediction markets have a unique set of needs around datasets and modeling. How do you price the odds of Jerome Powell raising rates, or Taylor Swift announcing a new album? Institutions will try to answer these questions with all the data sources and predictive tools they can get their hands on.

The big question for B2B is how quickly and aggressively institutional firms will enter prediction markets. Some firms like Susquehanna are known for being more creative, and they’ve already spun up desks for sports and event contracts. But I’d bet that large managers like Citadel and Bridgewater will be in wait-and-see mode. For them to enter a new asset class – and invest in new infrastructure, teams and operating methodologies – they must have confidence they’ll be able to deploy large sums of capital over years.

But right now, the prediction market space is in regulatory flux. Investors like Citadel see how quickly the Trump administration opened the door to prediction markets, and how quickly a court ruling or White House election could reverse course. That said, if prediction markets do emerge as a major asset class, major investors will enter the space and drive demand for B2B tools.

##

That brings us back to the very crux of this essay. Prediction markets are exciting because they have the potential to emerge into a massive new asset class, like the equities or options markets. And outside of Kalshi and Polymarket, there’s plenty of room for innovation across both B2C and B2B. But the entire category depends on how regulation shakes out, which only time will tell.

In the meantime, I’m paying close attention to the rise of prediction markets, and the Will Ventures team is actively investing in the space, both B2C and B2B.

If you’re building around prediction markets, please reach out. Our team would love to meet you!

Really interesting read. Depending on how the regulatory chips fall, prediction markets feel like the inevitable future